What is genomic phylostratigraphy?

Genomic phylostratigraphy is a method to date the evolutionary

emergence of a given gene (i.e. gene age inference),

typically done for all genes in a genome. In practice, one performs

homology searches against an evolutionarily-informed database such as

the NCBI NR.

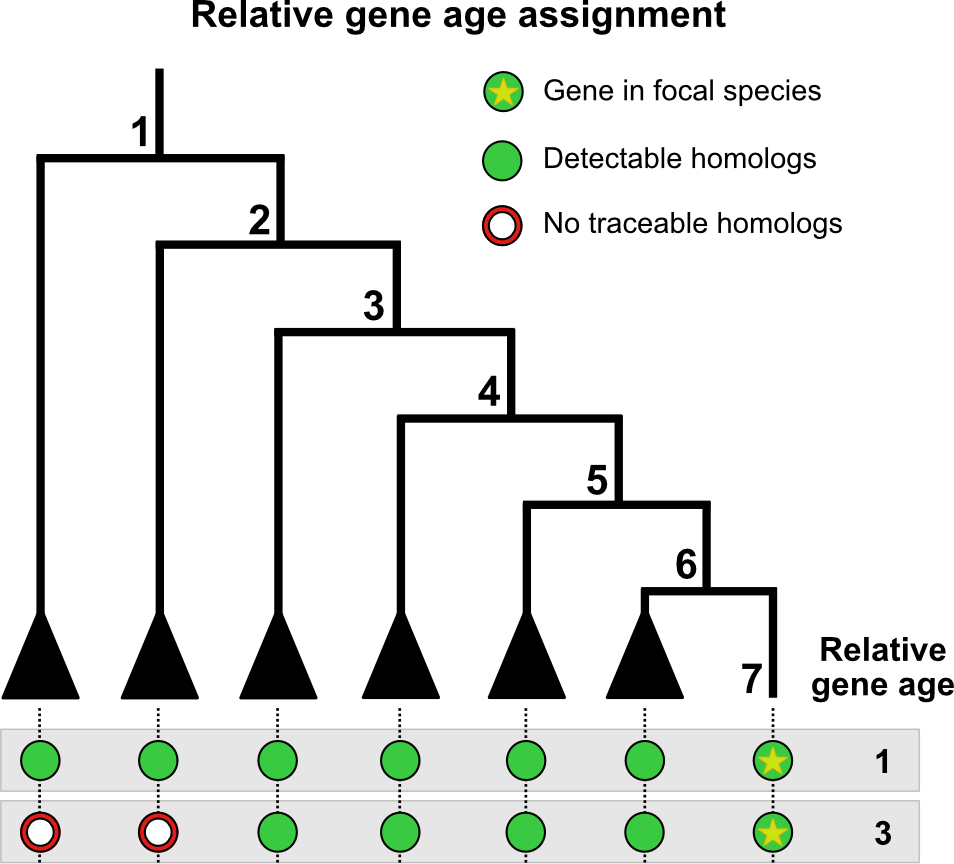

Overview of gene age inference. Here, we are searching two genes from the genome of interest against an evolutionarily-informed database. The first gene is assigned as relative age 1 since homologues can be found as far as node 1. The second gene is assigned as relative age 3 since homologues can be found only up to node 3. Adapted from Barrera-Redondo et al., 2023.

The output can be fed into myTAI and, combined with

expression data, is used to compute the transcriptome age index

(TAI). More specifically, gene age inference generates a

table storing the gene age in the first column and the corresponding

gene id of the organism of interest in the second column. This table is

named phylostratigraphic map (or phylomap).

For quick users, there are several recent software developed for gene

age inference such as GenEra

and oggmap. But

we hope you stay for the debate/discussion!

The debate

Despite its simplicity, since the first studies (Domazet-Loso et al., 2007), the method and concept underlying genomic phylostratigraphy has been subject to intense discussions (Capra et al., 2013; Altenhoff et al., 2016; Liebeskind et al., 2016; Domazet-Loso et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2018; Casola 2018; Weisman et al., 2020; Futo et al., 2021; Weisman et al., 2022; Barrera-Redondo et al., 2023; etc.).

The crux of the discussion focuses on the homology search bias, though several studies have also noted database bias (e.g., species representation and contamination) and evolutionary assumptions (e.g., Dollo parsimony).

Homology search bias

The first phylostratigraphy studies used BLASTp, which

performs pairwise protein sequence alignment, for the homology search

step. At the time of these study (late-2000s/early-2010s),

BLASTp was chosen as it balanced the requirements of

sensitivity and speed when performing sequence homology searches against

(at that time) a large databases.

The following discussions pertain to the potential biases with

BLASTp in particular and pairwise sequence aligners in

general.

BLASTp underestimates of gene age (for certain

genes)

Moyers & Zhang argue that the use of BLASTp genomic

phylostratigraphy

underestimates gene age for a considerable fraction of genes,

is biased for rapidly evolving proteins which are short, and/or their most conserved block of sites is small, and

these biases create spurious nonuniform distributions of various gene properties among age groups, many of which cannot be predicted a priori (Moyers & Zhang, 2015; Moyers & Zhang, 2016; Liebeskind et al., 2016).

However, these arguments were based on simulated data and were inconclusive due to errors in their analyses. Furthermore, Domazet-Loso et al., 2017 provide convincing evidence that there is no phylostratigraphic bias. As a response, Moyers & Zhang, 2017 published a counter-study stating that a phylostratigraphic trend claimed by Domazet-Loso et al., 2017 to be robust to error disappears when genes likely to be error-resistant are analyzed. Moyers & Zhang, 2017 further suggest a more robust methodology for controlling for the effects of error by first restricting to those genes which can be simulated and then removing those genes which, through simulation, have been shown to be error-prone (see also Moyers & Zhang, 2018).

In general, an objective benchmarking set representing the tree of

life is still missing and therefore any procedure aiming to quantify

gene ages will be biased to some degree. Based on this discussion Liebeskind

et al., 2016 suggest inferring gene age by combining several common

orthology inference algorithms to create gene age datasets and then

characterize the error around each age-call on a per-gene and

per-algorithm basis. Using this approach systematic error was found to

be a large factor in estimating gene age, suggesting that simple

consensus algorithms are not enough to give a reliable point estimate

(Liebeskind

et al., 2016). This was also observed by Moyers

& Zhang, 2018) when running alternative tools such as

PSIBLAST, HMMER, OMA, etc.

However, by generating a consensus gene age and quantifying the possible

error in each workflow step, Liebeskind

et al., 2016 provide a very useful database of

consensus gene ages for a variety of genomes.

myTAI.

Similarly, users can also retrieve gene ages from EggNOG database using orthomap.

Alternatively, users might find the simulation based removal approach

proposed by Moyers

& Zhang, 2018 more suitable.

BLASTp parameters are complicated

In these extensive debates, one aspect that is often missed and can

be directly corrected by an interested user is the

bioinformatics/technical aspect of using BLASTp or any

other BLAST-like tool for gene age inference. Namely,

BLASTp hits are biased by the use of the default argument

max_target_seqs (Shah

et al., 2018). The main issue of how this

max_target_seqs is set is that:

According to the BLAST documentation itself (2008), this parameter represents the ‘number of aligned sequences to keep’. This statement is commonly interpreted as meaning that BLAST will return the top N database hits for a sequence query if the value of max_target_seqs is set to N. For example, in a recent article (Wang et al., 2016) the authors explicitly state ‘Setting ’max target seqs’ as ‘1’ only the best match result was considered’. To our surprise, we have recently discovered that this intuition is incorrect. Instead, BLAST returns the first N hits that exceed the specified E-value threshold, which may or may not be the highest scoring N hits. The invocation using the parameter ‘-max_target_seqs 1’ simply returns the first good hit found in the database, not the best hit as one would assume. Worse yet, the output produced depends on the order in which the sequences occur in the database. For the same query, different results will be returned by BLAST when using different versions of the database even if all versions contain the same best hit for this database sequence. Even ordering the database in a different way would cause BLAST to return a different ‘top hit’ when setting the max_target_seqs parameter to 1. - Shah et al., 2018

The solution to this issue seems to be that any BLASTp

search must be performed with a significantly high

-max_target_seqs, e.g. -max_target_seqs 10000

(see https://gist.github.com/sujaikumar/504b3b7024eaf3a04ef5

for details) and best hits must be filtered subsequently. It is not

clear from any of the studies referenced above how the best

BLASTp hit was retrieved and which

-max_target_seqs values were used to perform

BLASTp searches in the respective study. Thus, the

comparability of the results between studies is impossible and any

individual claim made in these studies might be biased.

In addition, the -max_target_seqs argument issue seems

not to be the only issue that might influence technical differences in

BLASTp hit results. Gonzalez-Pech

et al., 2018 discuss another problem of retrieving the best

BLASTp hits based on E-value thresholds.

Many users assume that BLAST alignment hits with E-values less than or equal to the predefined threshold (e.g. 10-5 via the specification of evalue 1e-5) are identified after the search is completed, in a final step to rank all alignments by E-value, from the smallest (on the top of the list of results) to the largest E-value (at the bottom of the list). However, the E-value filtering step does not occur at the final stage of BLAST; it occurs earlier during the scanning phase (Altschul et al., 1997; Camacho et al., 2009). During this phase, a gapped alignment is generated using less-sensitive heuristic parameters (Camacho et al., 2009); alignments with an E-value that satisfies the defined cut-off are included in the subsequent phase of the BLAST algorithm (and eventually reported). During the final (trace-back) phase, these gapped alignments are further adjusted using moresensitive heuristic parameters (Camacho et al., 2009), and the E-value for each of these refined alignments is then recalculated. - Gonzalez-Pech et al., 2018

This means that if one study mentioned above ran a

BLASTp search with a BLAST parameter configuration of lets

say -max_target_seqs 250 (default value in BLAST) and

evalue 10 (default value in BLAST) and then subsequently

selected the best hit which returned the smallest E-value

and another study used the parameter configuration

-max_target_seqs 1 and evalue 0.0001 then the

results of both studies would not be comparable and the proposed gene

age inference bias might simply result from a technical difference in

running BLASTp searches.

BLASTp

with evalue 10 (default value in BLAST) and then

subsequently filtered for hits that resulted in

evalue < 0.0001 whereas another study ran

BLASTp directly with evalue 0.0001, according

to Gonzalez-Pech

et al., 2018 these studies although referring to the same

E-value threshold for filtering hits will result in

different sets of filtered BLASTp hits.

Alternatives to BLASTp

While BLASTP is considered the gold-standard tool for pairwise

protein sequence alignment, newer approaches (such as DIAMOND v2 and MMSeqs2) have been

developed, which can be used for gene age inference with the same

sensitivity - just much faster. Redesigned parameters in these software

can also overcome overlooked technical aspects of BLASTp

such as the -max_target_seqs.

Beyond pairwise protein sequence aligners, gene ages can also be inferred via structural alignment, using synteny information and using orthogroups.

Accelerated and sensitive sequence alignment

They retain the sensitivity of BLASTp while being

thousands to hundred-folds faster. This speed-up is crucial as sequence

databases increase in size. This is important for gene age inference and

DIAMOND v2 and MMSeqs2 have been

employed in various phylostratigraphic and phylotranscriptomic analyses

(either explicitly or under-the-hood in tools such as OrthoFinder, which

uses DIAMOND by default) (see Domazet-Loso

et al., 2022; Ma &

Zheng 2023; Manley

et al., 2023).

With DIAMOND, users can overcome the overlooked

technical aspects of BLASTp such as the

max_target_seqs issue by setting

--max-target-seqs to 0 (or simply

-k0). Furthermore, the --ultra-sensitive mode

can be employed, which is as sensitive as BLASTp while

being 80x faster (see Fig

1. in the DIAMOND paper).

GenEra, a

recently developed gene age inference tool, utilises DIAMOND v2 with

appropriate parameter settings by default. Users can also specify the

use of MMSeqs2 (Barrera-Redondo

et al., 2023). Potential issues such as homology detection

failure can be overcome by providing a pair-wise evolutionary

distance file as an input. Furthermore, users can set thresholds such as

for taxonomic representativeness to filter evolutionarily

inconsistent matches to the database, i.e. matches stemming from

database contamination or horizontal gene transfer.

Protein structure-based gene age inference

Advances in protein structure prediction have enabled the inference

of protein structure across the tree of life in a speedy manner. With

this new data, protein structure aligners such as FoldSeek

can be used instead of sequence aligners for gene age inference.

In the context of gene age inference, sequence-based alignments have

not been extensively studied compared to sequence-based alignments.

However, interested users can check out the FoldSeek option

for GenEra.

Synteny-based gene age inference

A recently introduced approach is called

synteny-based phylostratigraphy (Arendsee

et al., 2019). Here, the authors provide a comparative analysis of

genes across evolutionary clades, augmenting standard phylostratigraphy

with a detailed, synteny-based analysis.

Whereas standard phylostratigraphy searches the proteomes of related

species for similarities to focal genes, their fagin

pipeline first finds syntenic genomic intervals and then searches within

these intervals for any trace of similarity.

fagin searches the (in silico translated)

amino acid sequence of all unannotated ORFs as well as all known CDS

within the syntenic search space of the target genomes. If no amino acid

similarity is found within the syntenic search space, their

fagin pipeline will search for nucleotide similarity.

Finding nucleotide sequence similarity, but not amino acid similarity,

is consistent with a de novo origin of the focal gene. If

no similarity of any sort is found, their fagin pipeline

will use the syntenic data to infer a possible reason. Thus, they detect

indels, scrambled synteny, assembly issues, and regions of uncertain

synteny (Arendsee

et al., 2019).

Orthogroup-based gene age inference

The first studies in gene age inference used the framework of genomic

phylostratigraphy, where each gene of the focal species is compared

against a sequence database to find the most distantly related homologue

(Domazet-Loso

et al., 2007). Some more recent studies have instead inferred gene

age using the node in the phylogeny that contains all members of an

orthogroup.

An orthogroup is a group of genes descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor of a clade of species. This framework has been very useful for phylogenetic inference and comparative transcriptomics. Since an orthogroup is a subset of all sequence homologues in the given dataset, a gene can hit genes outside of its orthogroup (using the same parameters on a pairwise sequence aligner).

OrthoFinder (a

tool for phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics) is

commonly used in orthogroup-based gene age inference. The

result of OrthoFinder includes the files Orthogroups.tsv

(now depreciated)

and Phylogenetic_Hierarchical_Orthogroups/N0.tsv, which

have been used for orthogroup-based TAI studies (e.g. Ma &

Zheng 2023; Nishimiya-Fujisawa

et al., 2023). Incorporating these results into myTAI

can be done using orthomap

(see documentation).

Methodologically, it should be stressed that while

Orthogroups.tsv and

Phylogenetic_Hierarchical_Orthogroups/N0.tsv contain

orthogroups with more than one member (i.e. orthogroups with at least

one orthologue or paralogue), users should be aware that these output

files of OrthoFinder do not include singletons, which is a signature of

a novel or species-specific gene. To incorporate singletons, users

should include the genes in Orthogroups_UnassignedGenes.tsv

output or, alternatively, singletons in the Orthogroups.txt

file, and assign the singletons to the species-specific phylostrata in

the study.

The orthogroup-based approach seems to be motivated by an

assumption that the more restricted set of genes that consists of

orthologues and in-paralogues (paralogues that arose after the species

split) tends to have more similar attributes (e.g. conservation in

function and/or expression pattern) than the larger set of genes that

contains all sequence homologues. It follows that this framework should

better reflect the ‘gene age’. This assumption draws parallels to the

orthologue conjecture (i.e. orthologues tend to have more

conserved attributes than paralogues), which is heavily debated (Gabaldon &

Koonin 2013; Dunn et al.,

2018; Stamboulian et al.,

2020; etc.). In several cases, orthologues do not have more

conserved attributes than paralogues. Indeed, ‘shifts’ or

‘substitutions’ in the expression profile of paralogues that arose

before the species split are observed in single-cell studies (Tarashansky et al.,

2021; Shafer et al.,

2022).

Open questions

Regardless of the homology search algorithm choice, there remains some open issues with gene age inference.

Homology detection failure

Small and fast-evolving genes are often wrongly annotated as young

genes due to homology detection failure. This issue and

potential solution in the context of gene age inference have been

discussed by Weisman

et al., 2020.

An alternative explanation for a lineage-specific gene is that nothing particularly special has happened in the gene’s evolutionary history. The gene has homologs outside of the lineage (no de novo origination), and no novel function has emerged (no neofunctionalization), but despite this lack of novelty, computational similarity searches (e.g., BLAST) have failed to detect the out-of-lineage homologs. We refer to such unsuccessful searches as homology detection failure. As homologs diverge in sequence from one another, the statistical significance of their similarity declines. Over evolutionary time, with a constant rate of sequence evolution, the degree of similarity may fall below the chosen significance threshold, resulting in a failure to detect the homolog. - Weisman et al., 2020

Users can run their test, abSENSE

to detect the probability that a homolog of a given gene would fail

to be detected by a homology search. We note that a recently

developed tool GenEra

can automate abSENSE analysis for every gene in a given

genome and provide an output compatible with myTAI.

Dollo parsimony

Dollo parsimony, which precludes the possibility that an identical character (gene) can be gained more than once, is a major conceptual assumption for gene age inference (Galvez-Morante et al., 2024).

This assumption has been found to overestimate ancestral gene content (i.e., pushing more genes to be evolutionarily older) on simulated data, when compared to a maximum likelihood-based approach that allows a gene family to be gained more than once within a tree (via convergent evolution and horizontal gene transfer).

A suitable method to overcome this limitation is yet to be developed for user-friendly gene age inference.

Sequence contamination

As we amass more and more genomic data across the tree of life, we inevitably accumulate sequences that are taxonomically mislabeled (Steinegger & Salzberg 2020). These mislabeled sequences are thought to typically arise from sequencing contamination and biases gene age inference by overestimating the real age of the gene (i.e. as evolutionarily older).

The gene age inference software, GenEra, accounts for

potential contamination to some extent. Upstream software can be

employed to further address potential contamination but these are

typically applied to query genomes and not the database (see Balint et al.,

2024 and Nevers et al.,

2025).

To the best of our knowledge, while several bioinformatic solutions exists for query genome contamination, database sequence contamination remains a challenge.

Summary

Despite the ongoing debate about how to correctly infer gene age,

users of myTAI can perform any gene age inference method

they find most appropriate for their biological question and pass this

gene age inference table as input to myTAI.

To do so, users need to follow the following data format

specifications to use their gene age inference table with

myTAI.

As these discussions show, even when users rely on established procedures such as phylostratigraphy, the gene age inference bias will be present as ‘systematic error’ in all developmental stages for which TAI or TDI computations are performed. Thus, stages of constraint will be detectable in any case.

Since TAI or TDI computations are intended to enable screening for conserved or constrained stages in developmental or biological processes for further downstream experimental studies, even simple approaches such as phylostratigraphy can give first evidence for the existence of transcriptomic constraints within a biological process.

If researchers then wish to extract the exact candidate genes that might potentially cause such transcriptome constraints then I would advise to rely on more superior approaches of gene age inference as discussed here.